Leopold Kohn and Ernestine Kohnova (nee Diamant)

On a hot sunny Sunday, we set off to Cadca. This is the final week of the trip, Slovakia. Cadca is near the northern border of Slovakia, close to Poland. It is the place where the trains from Slovakia transporting the Jews to Auschwitz, stopped, and where their human cargo was handed over to the SS. It is also the family home of my grand-mother’s family – the Diamants. We are staying in Zilina, which we visited for the first time last year for the memorial event. This time, it is just our base for further exploration

The drive up the valley to Cadca is stunning, almost Alpine, with its tree covered mountains on either side and a lush green valley between. At times we drive next to a river and the peace and beauty on this quiet morning help me to understand why Ernestine (my grand-mother) might not have been able to settle in New York. Did she dream of a return to these green mountains from her tenement flat? Did the slow domestic pace of a small town where everyone knew everyone, where in every shop and round every corner was a friend, a relative, call to her from the frenetic streets of the Lower East Side?

Cadca is small and seems deserted when we arrive and park. We set off along a pedestrianised shopping street and branch off towards the cemetery; we are searching for the memorial to the Jews of Cadca. At the Catholic cemetery a few people are tending graves, the cemetery is vast and stretches away as far as the eye can see. It is a riot of colour, on every grave there are artificial flowers, little lanterns and big headstones. I am not sure how to find the memorial so ask an elderly lady, who is at the entrance and is enjoying an ice cream cone. I show her the website on my phone and in a mixture of Czech (me) and Slovak (her) we talk, she is very helpful and shows us how to find it, walking with us to the perimeter of the graveyard, and pointing to a small path behind a house, which we follow. It comes out on to another little road and there, in the midst of a small meadow, we see the memorial. It is completely quiet, just the stone memorial and a sculpture of a fire blasted tree trunk, symbolising the lives cut short. We read the inscription, “Here was situated for centuries the Jewish cemetery. From 1942-1944 the Jews of Cadca were deported to extermination camps and their community ceased to exist.” In the days that follow, I shall visit other memorials and even Auschwitz, but none will make me cry as these few lines did.

Most of Ernestine’s direct family emigrated to the USA long before the Holocaust, but this little town had been home to their ancestors and to others, for centuries – and in two years everything was destroyed. There is no sign of a gravestone anywhere, it is just a green field with a few benches, and right next door is a vast graveyard for Catholics, Christians who care for the graves of their own ancestors.

For these few days I am visiting absence and emptiness. On Monday we head for Bytca, to visit the archive. Appropriately it is situated in a derelict castle, I can hardly believe where I have been told to go. The open walkways round the abandoned courtyard are decorated with the remains of wall paintings, partially destroyed and flaking from the walls. Only the sign ‘Studovna’ keeps me walking, and there, sure enough, is a little archive office were I can scroll through microfiche and find the birth records of Alice and my grand-parents. I could have spent days there filling in the details of ancestors, maybe I shall return.. As we leave, opposite the castle, is the old synagogue – it is large and in a prominent position in the town, but it is derelict; the Jewish population, once central to the life of Bytca, no longer exists.

Tuesday, and the mission is Ruzomberok. The Jewish cemetery there has been moved to adjoin the Catholic cemetery, some old gravestones from the original cemetery in the town have been transported there and there are also new graves. I am hoping to see something of the Glasner family and also Helena Petrankova’s grave which, according to an online history of Ruzomberok’s Jews, is also there. The graveyard is on the edge of the town, on the slope of a hill and, like the one in Cadca, is huge and packed with brightly decorated graves. The Jewish section is at the very furthest point. There are a few graves, surrounded by overgrown grass and overlooked by a large memorial to those who died in the holocaust. There is a small dead snake on the path, so we pick our way very carefully towards the graves and soon I see the name Geiger, Alice’s mother’s maiden name. It is a family grave of the Glasner, Politzer and Geiger families. It contains thirteen members of the family. The main granite headstone, which should have been upright, has fallen down and lies across older graves. We scrape away the moss and dirt to find a couple more names, but have no way of knowing more than a few of those buried there. I search for Helena Petrankova, there aren’t so many to choose from, but I can’t see her. Then, I notice Simon Ackersmann, her father, and there, underneath but on the same inscription, is her name. Helena died in 1968, a few days after the invasion by Soviet troops. I try to find more information at the cemetery office, but they have none. We ask about the grass and how often they get visitors to the Jewish section. The lady explains how many cemeteries they have and how wet it has been, they will get round to it eventually. They only get one or two visitors a year to the Jewish graves, no wonder they see clearing a path to them as low priority.

My final destination on this voyage is, appropriately, Auschwitz. It is another blazing hot day when we arrive and we are booked on a six hour study tour. So much has been written about Auschwitz, but as well as seeing for myself, I want the answer to certain questions. I want to know what would have happened to Ernestine and Leopold, my grand-parents. And I do discover more detail, I learn that as they were deported in 1942, this was relatively early in the life of the camp and before Birkenau, the death camp, was built. They would have arrived at Oswiecim railway station, the direct train tracks under the watch tower to Birkenau were yet to be completed. They would have been marched to the camp and surprisingly for someone of Leopold’s age, he was chosen to “live” and be registered. This meant they were separated on arrival; Ernestine was not registered, she was directed straight to the gas chamber.

The gas chamber at Auschwitz has survived, the four larger ones at Birkenau were all destroyed. We can visit this one, I can stand in the room and try to think about what happened there. It is impossible, my mind just can’t take it in.

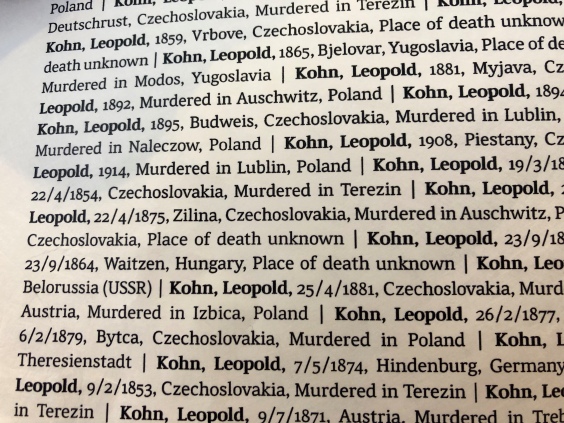

Leopold did not live for much longer, he might have been destroyed by the work and the conditions, maybe he gave up after losing Ernestine. I have strange thoughts. I am relieved that their journey from Zilina was such a short one, only a few hours, so many people travelled for days or even weeks in cattle trucks across Europe to reach there. Cruel as Auschwitz is, it is not as bad as Birkenau, and I am relieved they never had to see the full industrial machinery of death that it became. Strange how the brain adapts to horror, finding ways of working with and adapting to that once unimaginable reality. In one of the final rooms there is a book of the dead, listing 4 million of the 6 million Jews killed in Holocaust. I want to find Leopold’s name, I know it is there, but there are so many Kohns, so many Leopold Kohns that there isn’t time before the guide wants us to move on. Just as we are going, I spot his birthdate and place of residence – Zilina. We return in the lunch break to take the photograph. I don’t know why I so wanted to do that, I have other documents certifying what happened to him. I just felt in that place of horror I wanted to locate my grand-father, somehow to make that connection, as if being there I was finding more of him than just a name.

In the afternoon we visit Birkenau and I have not described a fraction of what we saw, but there is a moment beyond the camp, behind the remains of the four huge gas chambers when we stop in the welcome shade of dappled trees and read another of the memorials. We stand in front of a pool, it is a strangely peaceful scene, away from the crowds of tourists and our guide says, “These pools are full of human ashes.”

Auschwitz has millions of visitors. On the day we went, continuous streams of students, older people, soldiers from the Israeli army, people from all over the world passed through the barracks of misery and degradation, stared at the mechanisms of death, photographed the now iconic places of arrival and selection. They stared at the vast piles of human hair, shoes, brushes, the maps like spider webs that show the places from which the victims came, all converging on this one point. The crimes are remembered, and the victims too, but their worlds, the vibrant communities to which they belonged, are no more, preserved only in the furthest corners of rarely visited graveyards.

I have been following your blog with great interest, Liz, and find your posts moving and informative. I know your research is about piecing together your famiy story but your discoveries and observations resonate so much more widely. Following a week of D Day commemorations, we are reminded again of how important it is to listen, share and remember. In these days dominated by angry nationalislm, it seems the language of remembrance is our only common language

Our middle son, Tim (19) is traveling to Krakow next week with friends and will visit Auschwitz. This post has given him pause for thought. Thank you.

Evelyn

LikeLike

Very moving, Liz. I hope it has not been too sad for you. Jill x

LikeLike

Oh Liz, how incredibly moving but wonderful that you are breathing life into the history of your ancestors and Alice and friends.

Pete and I visited the grave of my Dad and Rory, which includes a commemoration of my Mum, on our way home from Wales. There is a very simple small flat gravestone which is a replacement of the original. Sean, Jackie, Pete and I replaced it a few years ago with simple but beautiful wording which gives me great comfort. I hope you can find comfort too in all of this.

With much love Anne

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

Such a journey dear Liz, I can barely imagine what it has meant to you but I’ve read and re read and been moved by your words. Till we meet.

LikeLike

This is so moving and fascinating, Liz. What an end to such an incredible trip.

I look forward to catching up when you’re back.

Tabitha

LikeLike

Interesting, moving and beautifully written

Andrew Cohen

LikeLike

A visit ultimately to Auschwitz could only ever be deeply disturbing, but for you now also inevitable. Once there, if course you had to find that record of Leopold’s name. Even the air is still in those places, I have found, and I remember – in the vast open complex of Buchenwald particularly, many years ago – the complete absence of birdsong.

You now have a great many experiences to process, along with much amplified knowledge. Coming home to England will probably also seem unreal.

LikeLike