I am standing in the darkened wings backstage. I am in group 2, waiting to walk out onto the stage and read seven names. I am holding my glasses, but when I get to the lectern, the names are in such large type that I don’t need them. I read out, ‘Leopold Kohn, 67 years old, Ernestine Kohnova, 66 years old, Ignacz Kardoš, 60 years old…’ There are four more names, people I don’t know and maybe who have no one left to read the names for them. Then I turn, bow to the screen where an endless roll call of names continues to scroll and go back into the darkness backstage.

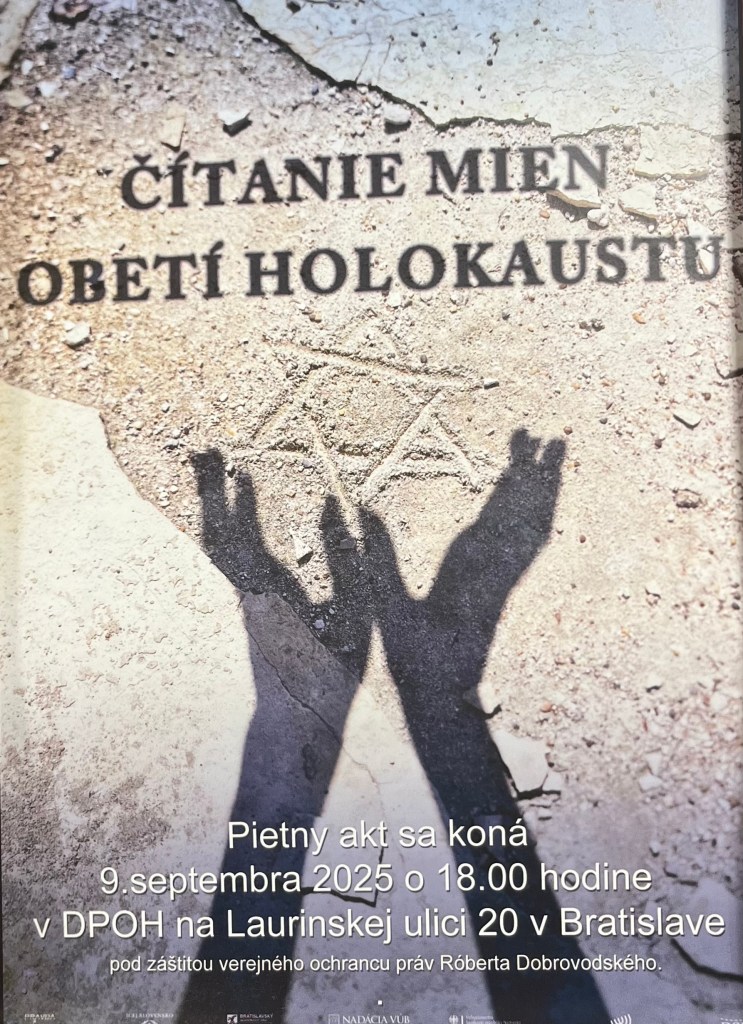

I am in a theatre in Bratislava and have just read out the names of my grandparents and of a great uncle. The date is September 9, 2025, 85 years to the day after the Slovak National government introduced the Jewish Codex. It was the law that defined what a Jew was and that excluded them from nearly every aspect of society. It was the law that prevented them from marrying non-Jews, from owning businesses and property, from taking part in the professions, from attending school, from owning a bicycle or a radio… It was the law that would lead to the Slovak government deporting its Jews, handing them over to the Nazis at the Polish border and paying them 500 Reichsmarks for every Jew they took.

After the reading, I return to my seat in the auditorium. The ceremony lasts two and a half hours and throughout, there is a never-ending scroll of names on the rear wall. After forty-five minutes, we are still on the letter B and by the end have not finished the letter M. When we get to the letter K, the whole wall is filled with the name Kohn. For most of my life I have lived in places where I am the only person with the name Kohn. On this wall, hundreds share my name. The reading of names is punctuated by music and some panel interviews. There are many different readers, but only three of us are reading the names of our relatives, the other readers are politicians, actors, journalists, priests, ambassadors … Towards the end I am interviewed about my family, alongside Vivianne, who has also travelled from England to read the names of her family. I explain that I am wearing my grandmother’s bracelet, the one she was given when she first emigrated to America and then gave to her sister, Hetty, when she returned to Slovakia in 1910.1

A hundred and thirty years since that bracelet left Slovakia, it has returned. I wore it as I read her name, Ernestine. She, like millions of others, was treated as less than human. But now I had been given the opportunity to read out her name in her own country and for her to be remembered, for the crime that was committed against her to be acknowledged. The other name that I chose to read out was that of Ignacz Kardoš (known as Imre to the family). He was Erwin’s (my father’s) paternal uncle and had paid for his education because Erwin’s parents could not afford to. At the end of the war, as a member of the US army, Erwin was at the liberation of Buchenwald, and he found Imre there and helped to return him to Bratislava. He survived for just a few weeks. I had never heard of him before I began my research, but he had given my father the greatest gift- education- and I wanted to honour him.

The penultimate event of the evening was the presentation of an essay prize to school students. Two of the winning students were from Žilina, my father’s hometown and, after the ceremony, I congratulated them and explained my father had been at school there over a hundred years earlier. He graduated in 1918 and went to study medicine in Prague. One of the students said she too wanted to study medicine, and I wished her luck. The circularity of the coincidence seemed appropriate.

The final event was the lighting of candles in the shape of a star of David. Many photographs were taken and then a woman came up to me and wanted to shake my hand. She thanked me for coming and said she had always been ashamed of her country’s behaviour in the war and was grateful to me for coming back. I had felt it was my honour, but I came to realise it was also important to many Slovaks to see the descendants returning and reconnecting with the past. It made me see both the ceremony and my relationship with Slovakia differently. It was as important for the Slovaks as for those of us returning.

I have had an ambivalent relationship with Slovakia. My first visit, in 2018, was for the reunion of survivors of Žilina’s Jews. Then too, I was grateful for the opportunity and for the care taken by the town to recognise its past, however, I was struck by the lack of knowledge or interest in the small memorials that had been placed in memory of the deportations. In Bratislava, it took me a while to find the memorial to the victims of the Holocaust and I still cannot quite get over the ‘Underpass of Memory’, or in Slovak Podchod Pamäti. In 1964, a large dual carriageway was built leading to a new bridge over the Danube. It drove straight through the Jewish quarter and was made possible by razing the city’s synagogue to the ground. A few posters stuck to the wall in the road’s underpass explain what happened and on a small square next to the underpass is an abstract sculpture with the word ‘Remember’ on the plinth in Slovak and Hebrew. Nowhere does it explain what needs to be remembered. Nowhere does it explain that the Slovaks deported their Jews.

On this visit, a few weeks ago, I was passing the memorial, when a large group of English-speaking tourists arrived with their guide. I stopped to listen, and was encouraged to hear her describe what had happened, and say it was a dark page in Slovakia’s history. She acknowledged that there are still Slovak historians who try to overlook or deny what took place. At the end, I went up to her and thanked her for her honesty and explained why I was there, we shook hands.

Slovakia may once again have a far-right government, whose president attended the summit in China alongside Putin and Kim Jong Un, but many of its citizens do understand the country’s past crimes and work for a better future. The Reading of the Names is in its sixteenth year, initiated and organised by Ľuba Lesna, whose play about Tiso, Hitler’s President, is still playing to full houses in Bratislava. And then there was the young English teacher, who made a seven-hour train journey from the easternmost part of Slovakia to translate at the ceremony and was making the same journey back the next day before a full day of teaching.

I had thought the ceremony would provide a sense of closure, but I think it was a beginning rather than an ending. It opened a door into new connections and relationships that I hope, over time, will grow.