We are in a semi basement in Žilina. Through the windows, high in the wall, we can see the legs of passers by on the pavement above us, strolling or walking briskly on a sunny Saturday afternoon. They have no idea we are here, beneath the street, but we have returned. We are in the basement where Vrba and Wetzler hid after their escape from Auschwitz. They, too, must have looked up at the ordinary life passing by above them and wondered when they would ever join it again.

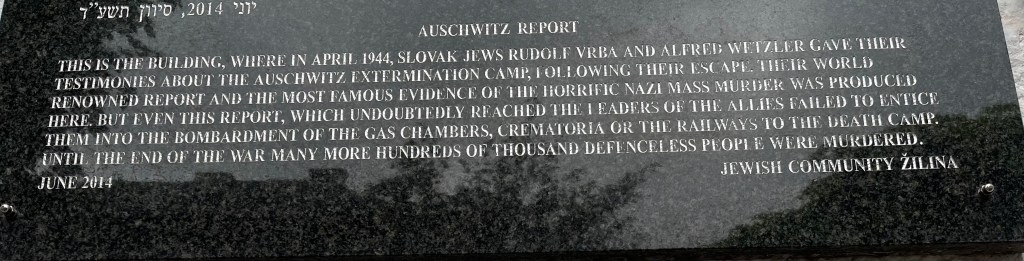

We are waiting for a short film to begin which will tell us about these two Jewish escapees from Auschwitz, who have recently leaped to fame as a result of Jonathan Freedland’s best-selling book. Those of us waiting in that basement room didn’t need his book to tell us their story, we were already connected with it. We, the children and grand-children of the Jews of Žilina, have returned for the annual reunion and remembrance event for those of our ancestors killed in Holocaust. This year, the week-end includes a visit to the basement in which the two men were hidden and in which they wrote out their testimony. The young woman from the tourist office, who shows us the film, speaks little English and, as it finishes, she is out of her depth when we all break out into questions and memories.

That small room contains the daughter whose mother brought food to the two men while they were in hiding there, and then the questions and connections multiply. We have come from all over the world – South Africa, Australia, Israel, Britain and, of course, Slovakia itself, drawn by a common heritage and keen to share names and histories. The young woman from the tourist office is used to school parties, not the actual returnees whose families shared the experiences that, to her, are history. She stands, slightly bewildered, as we all talk together with an intensity, born of the opportunity for a shared past. For us, those events are woven in grief and loss into our families and who we are, but in our everyday lives our history requires too much explanation. Here, it needs none.

We re-emerge into the Summer sunlight, all too aware that for Wetzler and Vrba, and our own families, that carefree ability to mingle in the streets and find a little cafe or bar for a break and a drink became an impossibility. The act of returning is complex and returnees are not necessarily met with a welcome. The two escapees with their stories of industrial mass slaughter and unimaginable horror met with doubt and incredulity and their story, once sent to the governments, elicited little help. After the war, when the few surviving Jews returned to Žilina, their former neighbours greeted them with suspicion, not wanting to give up the homes and businesses they had acquired. And what about us, nearly eighty years later?

We too are revenants, ghosts from the past, who for one week-end walk again across the squares, round the little streets and stone arcades searching for houses in streets that have changed their names, or car parks where once stood a family business, a strange pawn shop which had been a doctor’s surgery. The town is small, and there are about 100 of us, so we keep bumping into each other, greeting each other in a tiny reflection of what our past might have been, in a town where everyone was known. Comparing notes with others, I realise their families lived yards from my father’s surgery, and were probably his patients. We are all connected, our ancestors were shopkeepers, artisans, doctors, bankers, lawyers, hoteliers, we were woven into the fabric of the town and now we are adrift, scattered across the world. Only the graves and memorials remain and a few descendants who never left.

On Sunday we have the opportunity for a service in the old synagogue, it is hardly used now, so few are left, but on this day the rabbi for Slovakia, himself a refugee from Ukraine, will take a service of remembrance, one in which we can each name our lost loved ones. He explains it in Slovak and English as many of us are unfamiliar with the service, but there we stand, saying the names of fathers, mothers, wives, brothers, sisters and then, at the end, others we loved and lost. For the fraction of time in which their name is spoken they are alive again in Žilina. They may not have been religious and many of us are not, but the naming is powerful and moving and uplifting.

The final official event is in the memorial hall of the Jewish cemetery, where the walls are covered with the names of the lost. We walk first in the graveyard, which is being well cared for, grass mown, trees planted and the writing on the headstones re-engraved with the names of those who died before the war. Then we move into the hall and walk around the walls. I run my hand over the names of my grand-parents and talk with a woman I have only just met, explaining who they are. I say, “Auschwitz” and she points to the name of her mother and says, “Sobibor”.

When the ceremony begins, we have introductions and then a talk by the mayor who manages to strike the exact right note of respect and inclusion, acknowledging the central contribution of the Jewish community to the town. I can’t stop crying, silently, involuntarily. The tears just course down my cheeks unchecked and the next speaker is a survivor. He has come from Canada, but he speaks in Slovak and we listen to this old man, whose voice chokes as he describes his father being shot on the death march. For him, the passage of years has done nothing to diminish the loss. The young boy is ever present within him, however far he has travelled and however many years have passed. His loss speaks to our own, those we knew or never knew, except from photographs, an absence and a question. The room is heavy with loss, somehow intensified because it is shared.

The event is being filmed and the camera pans round to take in the room. We are the ghosts, returned from a lost world and on this Sunday morning, it seems as if we are welcome. Tomorrow we will be gone, back to the many new lives we have made, belonging and not belonging, because a part of who we are remains in this small Slovak town.

Very powerful, Liz. Well done! I hope there will still be more? If so, is it possible for you to change my email address within this group to juliaduschenes@gmail.com juliaduschenes@gmail.com ? I can pick those up so much more easily.

X

J

LikeLike

Lovely post Liz

<

div>Hope you are happily ‘home’ now

LikeLike

Oh Liz this had me

LikeLike

I can see that being able to share this real experience with descendants of other families who also share your history will have been deeply moving. You convey this very effectively.

LikeLike

The narrative is beautifully written It is descriptive and powerful

Very moving

An account of our get together in Zilina with descendands from all over the world.

LikeLike

This is such a powerful piece of writing, I was completely riveted by it. It vividly brings home the long term reverberations of those horrific times of brutal, incomprehensible persecution and the effects on generations. The response of people living there now is quite chilling and you wonder how much things have changed underneath. Beautifully written, Liz.

LikeLike

Dear Liz,

Thank you for sharing this moving – and beautifully observed and written – post. It sounds like quite an intense visit, though with some comfort too.

With warm wishes,

Mary

LikeLike

A poignant post. Hope to hear more in person…Can’t wait to hug you both.DianeSent from my Galaxy

LikeLike