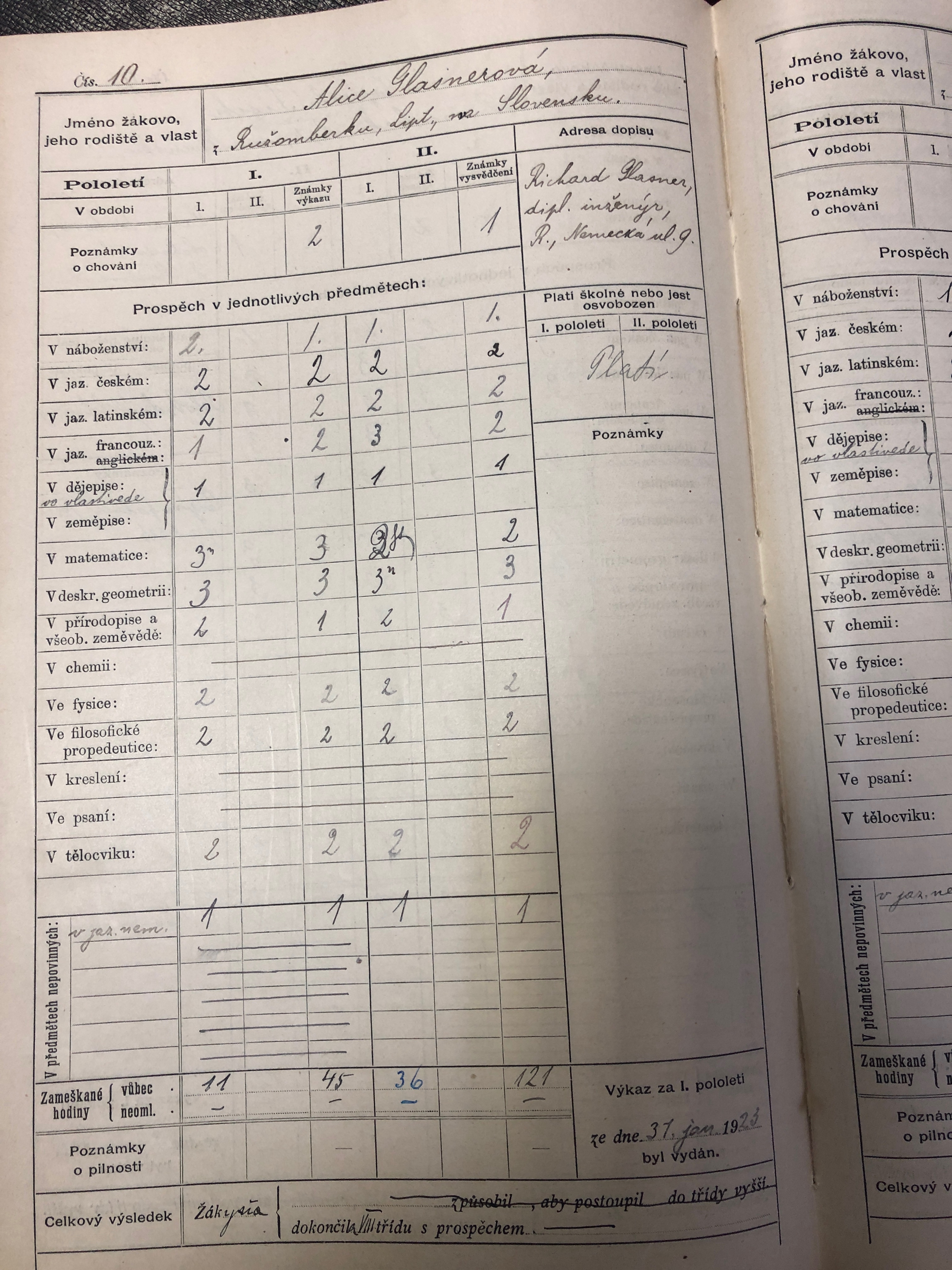

Value and meaning are in the eye of the beholder. What is worthless trash to one person is a precious symbol replete with meaning for another. So it was with an envelope, kept perhaps by accident, for the interest value of the stamp. Seventy years on, this envelope has connected with me and opened a window into the past.

I began the search for information about Alice and Erwin in 2017, hoping that someone out in the ether of the internet would read the blog and contact me. I have been overwhelmed by the responses I have had and the contacts I have made. Through this blog I have been contacted by relatives of Alice and the descendants of her closest friends. A month or two ago, however, I received a message on the blog page, from a stranger who had no connection with Alice or Erwin.

His name was Alan Scrivener and he explained that he had an envelope addressed to my father in America, from my grand-father, Leopold, who was still living in Žilina, Slovakia. The letter was dated May 1940. He offered to send me a picture of the envelope. One envelope, so easily thrown away, yet surviving, by chance.

It may seem as if an envelope alone could not communicate much, but that is not the case. It was addressed to my father at his work. Having left Czechoslovakia in December 1938, Erwin had passed his state board exams to practise medicine in the US and was working at the City of New York Welfare Hospital. I had researched the hospital, and this letter confirmed his employment there. Erwin’s experience in America must have revolutionised his outlook and medical knowledge. He had been trained in two of the oldest medical schools in the world, in Prague and Vienna. In New York, he was in a brand-new hospital, built in a chevron design to maximise light and benefitting from the latest research and techniques.

In the freedom and safety of America, with his horizons and opportunities expanding, he received this letter from Leopold. It wasn’t just from another continent; it was from another world. The back of the envelope is stamped Praskúmaná, which meant that it had been read and censored. Already, by the time Leopold was writing in May 1940, his life had been circumscribed. Jews had been excluded from all state and council occupations, the numbers of Jews allowed in professional occupations had been restricted, Jews who owned shops had been forced to hand them over to Aryans and had become employees in their own businesses. Leopold may still have been doing tailoring work, but all around him the antisemitic laws and propaganda of the new Slovak government were closing in.

Leopold and Ernestine could have left Slovakia and gone with Erwin to America, they had American citizenship, but they did not want to go. They had emigrated once when they were young and it hadn’t suited them, they had returned to Žilina. Now, in their sixties, they didn’t think they could be at risk, they had seen pogroms and persecution before, and they believed they could lay low and survive. How could they imagine what was to come? By the end of 1940 Jewish children would be banned from attending school and all Jewish doctors would be banned from practising, including Erwin’s closest friend, Artur Weil.

What had Leopold been able to write in that letter? Presumably he could say that he and Ernestine were well and perhaps give some news of other relatives. What had it felt like for Erwin to read of that other world and know that there was nothing he could do? As soon as he had turned over the letter to open it, he would have seen, not only the censored stamp but the name of the street on which his parents lived. Leopold’s address on the back of the envelope was now Ulica Adolfa Hitlera (Adolf Hitler Street). Before the war, the street had been named to commemorate the creation of Czechoslovakia: 28 October. That country no longer existed, the Czech lands had become a protectorate under the Nazis and Slovakia was under the rule of the Slovak National Party, whose president was the Catholic priest, Father Jozef Tiso.

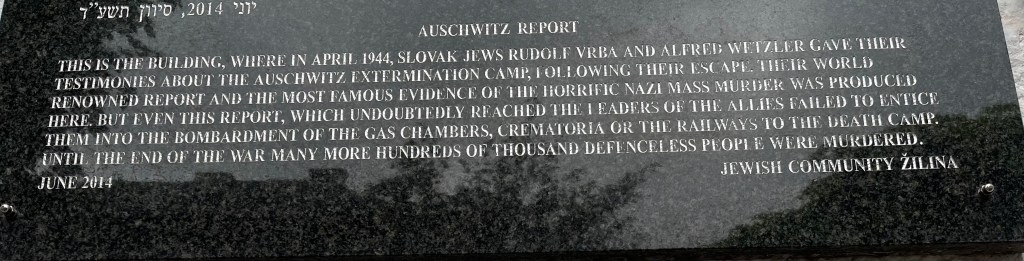

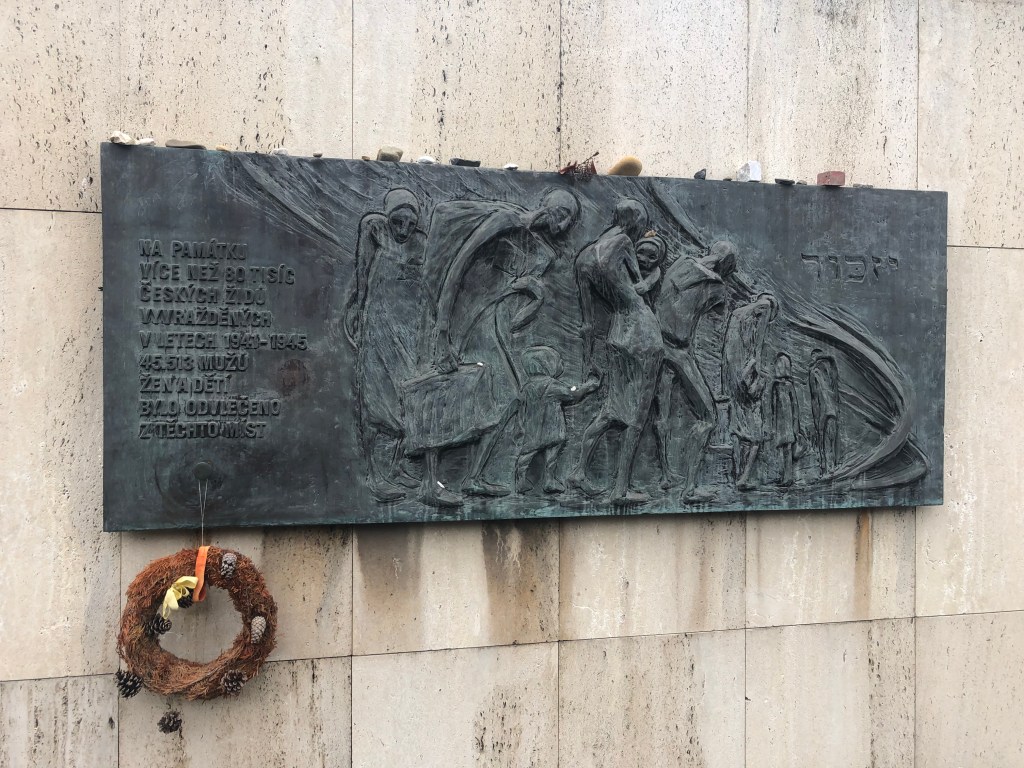

The shock of seeing Hitler’s name in Leopold’s address must have confounded Erwin, as it did me, when I read it. However, unlike Erwin, I knew that a decree of 14th December 1940 would forbid Jews in Slovakia from living in Hitler and Hlinka streets and squares. All premises in those streets occupied by Jews were to be vacated by 31 March 1941. When Leopold wrote the letter, he had ten more months before being turned out of his home. In June 1942 he and Ernestine would be on the train to Auschwitz.

Alan Scrivener collects letters and envelopes from those caught up in the Holocaust and tries to find the details of their lives and stories. He gathers up fragments from those whose lives were lost or transformed to preserve their memory and, by chance, along the way he provides a piece in a jigsaw for their descendants

Thanks to Peter Frankl for information about street names in Žilina and also his book Židia v Žilině, written with his brother Pavel Frankl (Nakladateľ Zbor Žilincov, 2008).

1.Eduard Nižnanský, Politika Antisemitizmu a Holokaust na Slovensku v Rokoch 1938-1945 (Múzeum Slovenského Národného Povstania Banská Bystrica, 2016).